Eskom facing R300-billion threat

Eskom has warned that municipal electricity debt could triple over the next five years, exceeding R300 billion by 2030 and threatening the power utility’s operational stability.

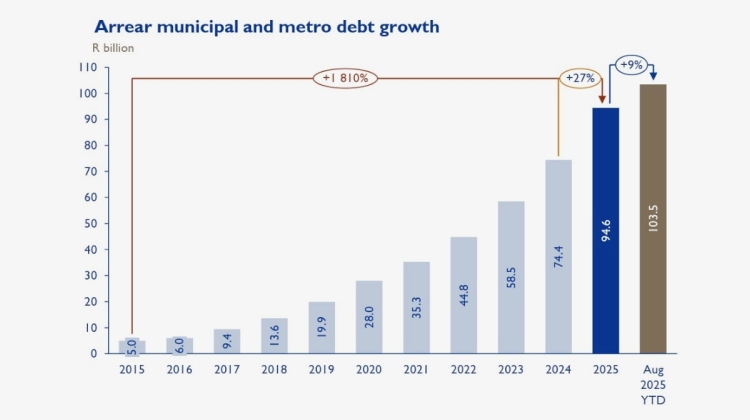

The power utility’s latest annual financial results revealed that by the end of March 2025, it was owed R94.6 billion for electricity sold to municipalities.

That represents an increase of 27% from the R74.4 billion in municipal arrear debt a year earlier. The debt continued to climb in the current financial year, reaching R103.5 billion by August 2025.

That figure is nearly 21 times greater than the mere R5 billion in municipal debt owed to the utility a decade ago.

Eskom said that without urgent and innovative interventions, the financial sustainability of its distribution business and the utility as a whole could be in jeopardy.

The utility said that the National Treasury’s municipal debt relief programme had failed to stem the escalating levels of arrear debt.

Launched in 2023, the inter-governmental effort sought to give defaulting municipalities a partial write-off of their Eskom debt in exchange for maintaining regular payments over 12 to 36 months.

By January of this year, 75 municipalities still owed more than R100 million to Eskom.

The biggest culprit was Emalahleni, which ironically is also the home town of many of Eskom’s employees due to its proximity to the utility’s coal power stations.

By May 2025, 60 of the 71 municipalities participating in the debt relief programme had received official warning letters from Treasury for continued failure to comply with the relief conditions.

Eskom has continued to maintain that an intergovernmental approach is necessary to resolve the issue.

The power utility has previously lost a court battle after it intermittently cut off supply to defaulting municipalities due to continued non-payment without consulting with national government entities for mediation.

Together with the Department of Mineral Resources & Energy, it is working on various solutions to address the issue, including distribution agency agreements (DAAs) and prepaid supply models.

“DAAs will support municipalities in ensuring sustainable local service delivery while contributing to Eskom’s financial sustainability through improved billing and revenue collection,” the power utility said.

In a DAA, Eskom takes over electricity supply services in a defaulting municipality, like it has done in Emfuleni.

That allows households and businesses to pay the utility directly for their power, while Eskom also becomes responsible for electrical maintenance.

The graph below shows how Eskom’s municipal arrears debt has increased between 2015 and 2025.

Electricity theft and billing issues exacerbating the problem

While Eskom and government entities have generally pointed the finger at municipalities for failing to maintain their bills, the issue could be far more complex.

Although numerous municipalities are grossly mismanaged and misappropriate funds, many are also struggling with high levels of illegal connections and ghost vending.

Eskom estimated technical and other losses, which primarily relate to electricity theft, rose 7% to R25.3 billion in its 2025 financial year.

The actual losses could be far greater, and in some cases, Eskom could effectively be passing the blame to municipalities for large-scale electricity theft carried out by insiders at the utility.

Eskom first acknowledged its online vending system (OVS) for prepaid electricity tokens was breached internally in its 2024 financial results.

While it would not respond to MyBroadband’s queries about the issue, it said that fraud linked to the OVS was “very low” due to improved physical security, cyber resilience, and operational controls.

MyBroadband has subsequently learnt that some prepaid meters may have a workaround that enables fraudsters to use tokens generated by Eskom’s OVS on STS-compliant municipal meters.

Households that use these tokens would consume electricity on a municipality’s distribution network without paying that municipality for the power.

Eskom has denied that using tokens generated by its systems can be used in municipal meters and vice versa.

A report by the South African National Energy Development Institute (Sanedi) has also flagged problems with billing accuracy, estimation processes, municipal debt, and bulk power-purchasing regulation in the country.

In an assessment of a dispute between Eskom and City Power regarding the city’s arrears debt of R3.2 billion, it found a combination of overbilling and underbilling.

On Eskom’s side, it found the power utility’s estimates failed to consider load-shedding effects and violated National Rationalised Specifications standards.

City Power’s meters were often found to be misconfigured, and mock billing practices were deeply flawed. These inaccuracies have created gaps for prepaid electricity thieves to go undetected.